Feminism

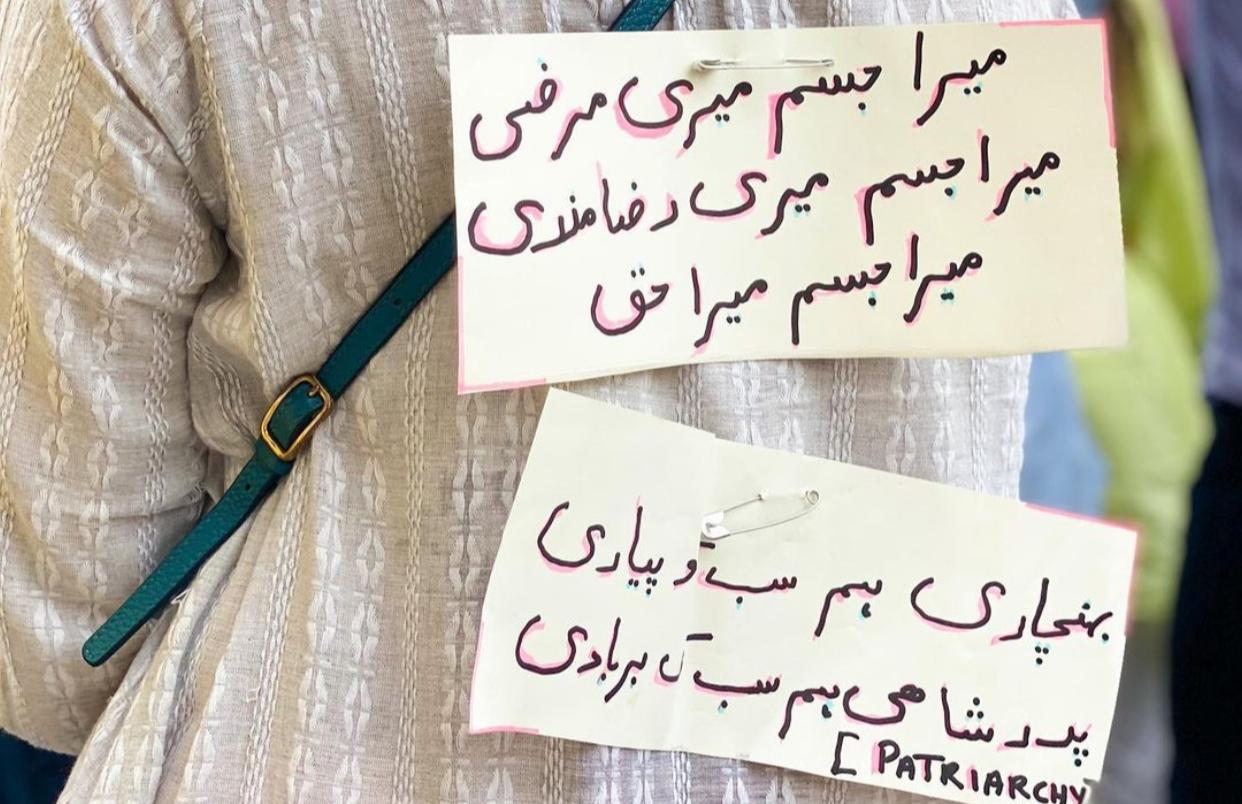

Feminism—a word that strikes fear, sparks controversy, and is often misinterpreted in our society. if you belong to a third-world Asian country with a middle-class background, you probably have a certain image in mind when you hear the word feminism—a rich, middle-aged woman in Western clothes, holding a placard that reads ‘Mera Jism Meri Marzi’ or ‘Apna Khana Khud Garam Karo.’ But is that really what feminism is about? Why is it painted this way? Is it truly as bidding as people make it seem? Why do women’s rights feel so threatening? Are they really that unbearable?

The first time I heard the word feminism was on TV, during a news broadcast covering Aurat March. I saw passionate women holding banners demanding equality—bold words, strong voices. Many of them seemed well-educated and from privileged backgrounds, but their slogans spoke of struggles that go beyond class. At first, I perceived it negatively. I thought—these women don’t need equality; they must already have it. But over time, I began to see the bigger picture. Oppression isn’t confined to one class or background—it exists everywhere, in every society, whether rich or poor. These women were not just fighting for themselves; they were raising their voices for those who couldn't. They were speaking for the women who are silenced before they can even dream of demanding their rights.

In Pakistan, approximately 1,000 women are killed annually in the name of "honor." In India, over 31,000 rapes were reported in 2022, equating to about 86 cases daily, with conviction rates hovering around 27-28%.Many cases in South Asia go unreported due to stigma and fear. Street harassment affects 79% of Indian women, and 40-60% of working women face abuse in their workplaces. They are not even safe in their own houses, not even children. Despite this, survivors are often blamed instead of protected. Phrases like "Kapray kya pehnay thay?" "Tali aik haath se nahi bajti”, and "Tum bahir hi kyun nikli thi?" are common excuses. We remember the Motorway Rape Incident that occurred in Pakistan, instead of ensuring justice, even the police questioned why a woman was traveling alone at night.

As of 2023, women constitute approximately 49.58% of Pakistan's population. However, the female literacy rate stands at 51.9%. This means that approximately 48.1% of women are illiterate. Reports indicate that approximately 1,000 girls from religious minorities are forcibly converted to Islam in Pakistan each year. Notably, most of these victims are minors under the age of 16, abducted, converted and then married to their kidnappers.

Menstruation, being a natural biological phenomenon, is viewed as something to be ashamed of in our society, silencing and stigmatizing women. Hundreds continue using unhygienic substances due to economic limitations and unawareness, while cultural taboos brand them as unclean. Instead of receiving care, they are expected to endure the pain quietly. Despite its inevitability, society refuses to acknowledge the need for education, accessibility, and dignity in menstrual health, turning a blind eye to the struggle’s women face.

But feminism isn’t just about women—it is about dismantling a system that suffocates everyone. It is about breaking the chains of patriarchy that not only oppress women but burden men with toxic masculinity. From a young age, boys are told "Mard bano, don’t cry” forcing them to suppress their emotions and shoulder impossible expectations. Men suffer under the weight of financial pressures, emotional repression, and the demand to be providers without the right to vulnerability. Feminism fights against these norms, advocating for a world where men can be human instead of constantly performing masculinity.

Yet, despite its true essence, feminism is twisted into a weaponized term.It is regarded by many as a threat to religious and cultural values. An excellent example of such misinterpretation is the Aurat March slogan "Mera Jism Meri Marzi." People have reacted with outrage against it because of purposeful distortion—people interpret that it encourages promiscuity when, in fact, it's a declaration regarding bodily autonomy. It is a demand for consent, the right to make personal decisions without coercion—whether it be about marriage, clothing, childbirth, or simply existing without fear. It is not an attack on religion, nor is it about rejecting tradition, it is about rejecting force. Equally, "Apna Khana Khud Garam Karo" is ridiculed as trivial, but it identifies the very entrenched gender roles that ensnare women in unwaged domestic work. A woman's value in most homes remains determined by how well she can serve, her life reduced to drudgery and childcare as men are exempted from simple self-reliance. The slogan is not about a heated meal, it is about challenging the idea that a woman’s place is in the kitchen while a man’s is everywhere else.

Yet, for centuries, women have been painted as delicate, unintelligent, and uninterested in anything beyond the trivial. History, yet again, takes a different tune. Women have spearheaded each sector, whether education or science, politics or literature. Fatima al-Fihri was the founder of the world's first university and Savitribai Phule a pioneer in the cause for education among women. Marie Curie changed science forever with discoveries made in the realm of radioactivity, while Margaret Hamilton's programming allowed human history's maiden footprints upon the moon. Arfa Karim was a child computer, while Ada Lovelace's contribution paved the way for the development of modern computers. Fatima Jinnah and Benazir Bhutto made space for women in politics, while Malala Yousafzai keeps pushing for the very basic right of education. Literature has also been influenced by women who used words as weapons—Jane Austen, Virginia Woolf, Ismat Chughtai, and Parveen Shakir all defied conventions in their works, while Anne Frank's diary is a lasting tribute to courage. From warriors to poets, from leaders to revolutionaries, women have re-written history time and time again, proving that intelligence, courage, and ambition are not feminine traits.

But even that, it seems, is the work of men—men who have fenced themselves in—closed them into homes, muffled their voices, and withheld space from them to think, to dream, to make choices. How can a woman be made to grow if she is not even given the simple liberty of existing on her own terms? When her mind is dictated , her body manipulated, and her dreams belittled, is this then a matter of ability? Or is this just a system designed to keep her in smallness?

Author and Researcher: Ayesha Anwar